Hvordan falske nyheter, podkastdramaer og en fiktiv onkel inspirerte Inkles TR-49

Inkle Studios' narrative director Jon Ingold created a detailed backstory for his latest game, TR-49. The story involved hidden lockboxes, family secrets, and a mysterious great uncle who might have worked for Britain's codebreaking unit during World War II. It contains the elements of a spy drama, but it is not true. Ingold confirms the story is a fabrication, created for the game.

The fiction is anchored in a small piece of reality. In 2014, Ingold was a math consultant for the film The Imitation Game, a biography of codebreaker Alan Turing. While on set, he saw a photograph that included the indistinct features of a tall man. In the corner of the photo was the code "TR-49." That image provided the seed for the fictional great uncle and the game's title. The code faded from his memory as Inkle went on to create games such as Heaven's Vault and A Highland Song.

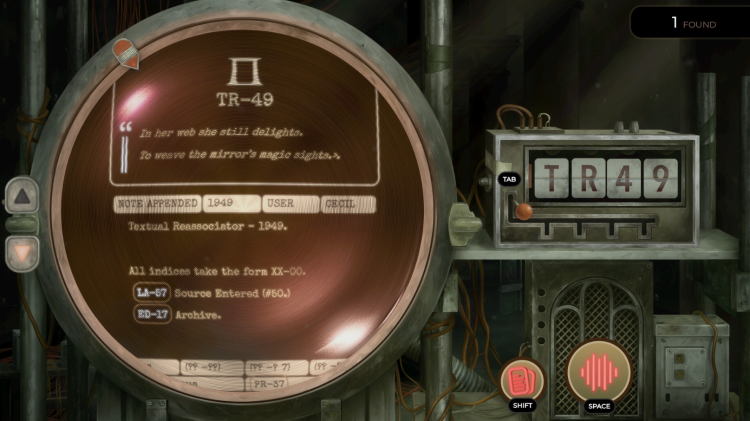

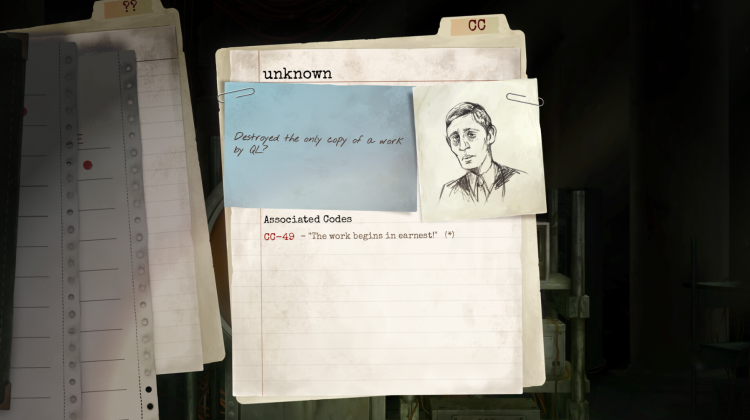

As we reported earlier, Inkle has taken an unexpected turn with TR-49, a project that moves away from its familiar mix of folklore, myth, and interactive narrative. This time, the studio focuses on a found-footage concept built around 50 mysterious World War 2-era books discovered in an attic, and the work of decoding their scrambled pages. The game blends audiobook delivery with deduction mechanics, drawing on historical detail and the atmosphere of lost archives.

Via Polygon’s review, the idea for a code-based puzzle game occurred to Ingold after he played deduction games and thought about combination locks. He found William Rous's Itch.io game Type Help, a mystery solved by typing codes relevant to the story. This led to his own concept of a game where players use cards from a library rolodex to find a stolen book. He built a prototype in Ink, Inkle's narrative scripting language, to see how the game might flow. The team prototypes any idea they like, whether it becomes a full game or not. The project was an experiment that Ingold did not intend to sell and was first envisioned as a physical game with actual cards.

The experiment continued to expand. Ingold began to see possibilities beyond the initial concept. He sketched out a conversation for the beginning and an ending. He realized that deduction games are typically about past events, not the present moment. As a storyteller, his interest is in what is happening right now. The basic premise involved a young woman finding a book by using clues from other books. Ingold struggled to find a way to combine the story of the books with the story of the person searching for them without one obstructing the other. His interest in scripted podcast dramas, like The Magnus Archives, gave him an idea. He decided to make the characters audible voices, creating a separate channel for storytelling that would not interfere with the gameplay.

Ingold showed the build to Joseph Humfrey, Inkle's other co-founder. Humfrey played it and gave his honest feedback.

"He played it for a bit, and said, 'it's a bit boring, to be honest.' And I was like "Yeah… It's just books, isn't it?"

— Jon Ingold (Polygon)

The prototype needed a more engaging interface. Ingold had been considering an "odd machine" concept for a while and had even prototyped a game around such a device a year earlier. The team decided to revive that shelved idea, turning the machine into the game's central interactive element. The project also served as a test case for building a game in Godot, a development engine the team wanted to learn. With a story, gameplay, and puzzles, the project began to resemble a commercial video game, but the plan was still to release it for free. It remained an experiment.

TR-49 continued to grow. Humfrey and artist Anastasia Wyatt worked to give the machine a tactile presence. It originated from Ingold's idea of physical rolodex cards, but Humfrey also enjoyed making a toy-like object that people could manipulate to get unexpected results. The machine makes a sound like a library microfilm machine when it brings up a new book. It has a clunky lever and a control dial. Humfrey created the dial's grinding metal sound by running a knife sharpener across a butter dish. The machine's design includes cords running in every direction and a retro-style speaker. The tactile element extends to its function; the player is told the machine literally eats books to record them, shredding the pages.

This detail about the machine destroying books connects to the game's core themes. Ingold was thinking about Christopher Nolan's film Oppenheimer and the discovery of quantum mechanics. He saw a parallel between the way science revealed a more opaque and less understandable universe and the central conflict of a Lovecraftian story.

"Science really ruined the idea of the physical universe, and that's just such a brilliant setting for a Lovecraftian story, this idea that it's not Cthulhu ruining reality. It's quantum mechanics."

— Jon Ingold (Polygon)

The game includes ideas about authoritarian regimes and organized religion's opposition to new concepts. The unifying theme that emerged is revisionism. The game explores the nature of truth in an age of fake news and social media. The question of who determines what is true and how it is remembered became the soul of TR-49.

With the game's purpose defined, Ingold reviewed the text and realized all the speakers sounded like him. He spent a day rewriting everything, giving distinct voices to each author in the game. He invented most of the authors and books but also included snippets from real-life writers. The game opens with a quote from Tennyson's poem The Lady of Shalott, about a woman in a tower who sees life only through a mirror.

"I was like, wait, he's talking about an iPhone! He's literally talking about doomscrolling on an iPhone. That was too good to be true. It had to go in."

— Jon Ingold (Polygon)

The entire development process took about nine months. Ingold finds it hard to believe the project became the studio's most successful launch. The team finalized the core playable component early, spending the rest of the time on enhancements. He believes there is an audience for deduction and adventure games that mainstream studios are not serving. He recalls working at Sony Computer Entertainment of Europe in the 2000s and pitching a murder mystery game.

"They said, 'Oh, they don't work because people get stuck and they can't do them.' So we just don't even try."

— Jon Ingold (Polygon)

The availability of online forums and guides means getting stuck is no longer a significant issue. Ingold suggests the real reason companies like Sony struggle with the genre is different.

"Sony can't make a murder mystery because a mystery is really an interface game. It's about paper and details and facts and organizing those facts together. And if you're making a big, AAA-budget game, you've got to have a character, you've got to have a world, you've got to have an art style. You've got to have all of that stuff just to sell the product and make it feel big-budget. But those things get in the way of the investigation. It's just like a piece of paper and you've got everything you need on it, and it's you versus the puzzle. And I don't think AAA games can do that, because they can't say 'that's what this game is' to the audience. But indies can."

— Jon Ingold (Polygon)

The definition of what qualifies as a video game has changed over the last 15 years. Ingold points to Gone Home, which received praise for using AAA concepts on a budget, and The Roottrees Are Dead, which has no main character and looks like a website. He notes that the design of these games is not new. The change is that audiences can now get excited about a game that doesn't have an avatar. This shift in the market has made a lo-fi approach feel like a real gaming experience.

TR-49 is available to play on PC through Steam.

3 gratiskasser og en bonus på 5 % på alle kontantinnskudd.

5 gratis saker, daglig gratis og bonus

0 % gebyrer på innskudd og uttak.

11 % innskuddsbonus + FreeSpin

10 % EKSTRA INNSKUDDSBONUS + 2 GRATISSPINN PÅ HJUL

Gratis case og 100 % velkomstbonus

Kommentarer